A Former Black Panther Party Leader Reflects on Her Revolutionary Work

A Former Black Panther Party Leader Reflects on Her Revolutionary Work

Among the many memories former Black Panther Party leader Ericka Huggins has from her time in the revolutionary organization, leading the Oakland Community School is one of her fondest. Huggins, who spent 14 years in the Party — the longest of any female leader in the organization — was the director of the school. “Those were some of the best years of my entire life. We educated elementary-age students about [their history] and their place in their great place in the world.” she says. “We led with love.”

As a human rights activist and educator, Huggins has always used that approach in her work. She was one of thousands who attended March on Washington, and even then, at the age of 15, she was profoundly affected. That moment inspired her to “serve people for the rest of [her] life.” Huggins later joined the Los Angeles chapter of the Black Panther Party in 1968 with her husband, John. Soon after, tragedy struck the family. In 1969, three weeks after the birth of their daughter, John was shot and killed. Four months later, Huggins and Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale were arrested and charged with conspiracy in New Haven, Connecticut, where they started a Party chapter. “Free Bobby, Free Ericka” became a rallying cry across the United States. They were acquitted, though Huggins served two years in prison while awaiting trial.

After her release, Huggins became a writer and editor for the Black Panther Intercommunal News Service before leading the Oakland Community School. Later, she developed programs to support LGBTQ+ youth and adults living with HIV/AIDS in the Bay Area.

Today, Huggins, 72, continues her activism as a facilitator for World Trust, a social justice and equity movement–building organization, and is a keynote speaker through SpeakOut.

Huggins spoke to ZORA about Black Lives Matter, sexism and sisterhood in the Black Panther Party, and the time Maya Angelou and James Baldwin visited the Oakland Community School.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

ZORA: At what moment did you know you wanted to join the Black Panther Party?

Ericka Huggins: I was a student at Lincoln, a historical Black university outside of Philadelphia. I read about the Black Panther Party in Ramparts, a magazine that no longer exists. In this article I read, the Party said it is for all poor and oppressed people. I knew that the Black Panther Party started with two young African American men [Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton], but for African American people to say, “For all poor and oppressed people,” I knew that meant Indigenous people, Latinx people, Asian people, and also poor White people. I wanted to be a part of such a huge movement, such a huge collaboration among human beings. My best friend John Huggins and I left school and drove across the country in his little car to join the Black Panther Party. That was in 1967.

The work of the Black Panther Party was laborious. In a previous interview, you said that members worked 19-hour days. Tell me about the moments of joy you found in the doing.

We felt joy when we saw the gratitude and the faces of people with all of our community survival programs. Or when the elders would come to free food giveaways and just smile and nod at us, as if to say, “You are doing good work.” We knew their conditions. We didn’t blame them for their own poverty. That’s something that has been a really ugly theory throughout the history of the United States: If you’re poor, it’s your fault. And there are even people of color who believe that that’s true, who believe in the bootstrap theory. But we knew that people didn’t have boots, or they would be pulling themselves up. So, we created 65 community survival programs to support the community, to uplift the people. And the joy was always there. I met the most phenomenal, incredible, compassionate, empathic men and women in the Black Panther Party.

I got to run the Oakland Community School, which was the flagship program of community survival programs. Joy was there too. The school was student-centered, community-based, and tuition-free. The children there were loved.

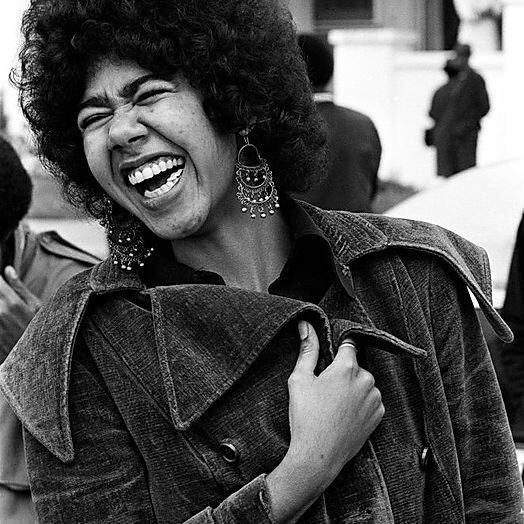

Photo: Stephen Shames Collection

Photo: Stephen Shames Collection

Maya Angelou and James Baldwin were among the many guests to visit the school. What were those experiences like?

Maya Angelou, who became a friend and mentor to me, heard about the school when she lived in Berkeley. She came and read poetry with the students. It was fantastic to have her there. She said that when she was growing up in the South, she would’ve given anything to have a school like this.

When Maya left that day, she hugged me and she said, “We have work to do. All the children should have a school like this, Ericka. Can we create something in Oakland, you and I?” I said, “Another school or a program?” She said, “An after-school program for public school children.” And I said, “Yeah.” We created the Oakland Afterschool Program in about three different public schools, [focused on] the arts and homework. Maya Angelou secured the money for it from the Bay Area Black United Fund. I told Maya that we’d gone to them [for funding] before. She said, “Dear, let me go to them.” She got the funding for the program. It was glorious.

Also, before Maya left that day, she said, “Ericka, I’m coming back, and I’m going to bring Jimmy.” And there was only one Jimmy she could’ve been referring to: James Baldwin. And when he came, oh my goodness, oh my goodness. He loved the school. It was in his eyes. He would step into a classroom and see the children, and he would just mutter something like, “My God.” He just loved how much they were loved and what they were learning and how attentive they were.

When we finished that day, he turned to me with big tears in his eyes and he said, “Can you imagine what my life, what every child’s life would be like if they had a school like this?”

“If we don’t recharge our batteries by taking care of our minds, our hearts, our bodies, we won’t be able to be in it for the long haul.”

You’ve said that the Black Panther Party changed your understanding of generosity. What would you tell Black women about being generous to ourselves while working to serve the people?

The human body is a little ecosystem. We can’t keep pushing it without giving it nutrition, water, and rest, without giving it a way to clear the emotions that accumulate over time, especially when you’re out there on the front lines. If we don’t recharge our batteries by taking care of our minds, our hearts, our bodies, we won’t be able to be in it for the long haul.

So, when I think of the front-line people, wherever they are in the world, whatever that front line is, I think about the breath—how important it is to pause and breathe. Even if you have an hour to sit somewhere and be in nature or walk in nature, which is very, very important. Or hang out with children or look in the eyes of a baby. You can at least sit for two minutes and just become aware of your breath and the power of it to help you reset.

We have to understand that these things, like rest, are built into the human being at birth. It’s not something we learn by accident. It’s just that our schools and our other institutions in society don’t remind us.

So true.

The children at Oakland Community School meditated every day for three minutes. They loved it. [Years later], I interviewed many of them, in their late forties and early fifties, for a thesis I was writing. That was one of the main things they remembered.

What is the role of meditation in social justice work as a tool for change?

It is a tool for change because of what it does for the person who practices meditation. It can be very simplistic. Sit and breathe. Do so with a mindful understanding that you are right here, right now, doing the work that you do, in the body that you’re in, with the mind you have and the emotions that you have.

Unraveling, anxious, fearful, angry: All those are human emotions. I have had them, and before the day is out, I could have them again. But which ones are going to keep you moving forward? Meditation brings freedom on the inside. It brings me clarity. It stokes the fire of compassion. It helps me to resolve problems as best I can or to figure out who to call if I can’t do it by myself.

What are your views on abolishing prisons and defunding the police?

As a person who was formerly incarcerated and also in solitary confinement…there is no benefit in it, none. It’s isolating, it’s warehousing, and it’s punishing. I was separated from my daughter and only able to see her for one hour each Saturday [while I awaited trial]. Solitary confinement is cruel and unusual punishment under the law.

Then, about defunding the police — that’s an accurate thing to look at. Why are police going to knock on the door after being told that there’s a call about a domestic dispute? They’re not trained to do that. Social workers can do that. Counselors can do that. Maybe in tandem with a police officer if the situation is exacerbated. I think we need to slow down and think about these things and look at what other countries are doing. There are places in the world where the police departments, as they knew them, have been replaced with something new to better serve the people.

Members of the Black Panther Party experienced a lot of loss at a very young age. The average age of a Party member was 19. After the birth of your daughter, your husband, John, was killed. You were imprisoned, as were many of your comrades. Being so young and grappling with so much, how were you able to move through the grief?

First, by consciously being aware that I was grieving. I didn’t know just how deep that grief was until I sat still in a prison cell. That was the precursor to me getting a book that I asked for and reading about how to do yoga poses. The cell I was in was so tiny, and I didn’t have regular walks. I got this book and it said, “After you stretch your body, sit still a while and breathe.” That’s what I did. That is what gave me access to all these qualities that were in seed form inside me. One of those qualities is resilience.

You can’t be resilient unless you’re willing to look at what it is that is holding you back or what it is that’s keeping you from bouncing back. I had to look grief in the face. I had to move through all of its seasons. It took years to do that fully, but I was able to begin. I was really young when I learned all of these things. I don’t wish this way of learning on anyone, but I am glad that I learned that I need to pause.

When I watched the video of George Floyd being murdered… I was not surprised. I wasn’t fearful. I wasn’t angry. I was just sad. I knew that I had to go back into this place in myself, there, in between breaths. For me, that’s where resilience can be accessed. I sent all kinds of good wishes and uplifting thoughts to his family. Then, when I heard about Breonna Taylor, I intentionally looked at her photograph and did the same thing for her mother, family, friends. I kept doing that whenever I would hear another horrific thing. I go back to what is life affirming.

‘Free Bobby! Free Ericka!’ demonstration, co-sponsored by the Black Panther Party and the Women’s Liberation Movement, New Haven, Connecticut, November 22, 1969. Photo: Bev Grant/Getty Images

‘Free Bobby! Free Ericka!’ demonstration, co-sponsored by the Black Panther Party and the Women’s Liberation Movement, New Haven, Connecticut, November 22, 1969. Photo: Bev Grant/Getty Images

Many people look at the Black Panther Party as a major influence for Black Lives Matter. How would you describe the lineage between the two movements?

If you think of it like the ebb and flow of the ocean, the Black Panther Party was a wave. Then, the Black Lives Matter network is a wave. There are also all kinds of organizations that don’t hit the news. The protests are a wave that flows out of the continual abusive treatment of Black and Brown people. I don’t think of anything in a linear fashion. It’s more fluid.

I think Alicia Garza knows whose shoulder she stands on, but there are a lot of shoulders, not just the shoulders of people of the Black Panther Party. The Black Panther Party knew whose shoulders they stood on. When I look back, I can look at Rosa Parks and Fannie Lou Hamer and all of the other people who’ve done good work prior to and during the time of the Black Panther Party. I don’t think it’s “there was this and then there was that.” I think it’s all one continuous thing.

Who are a few activists and organizers we should learn from, right now?

Patrisse Cullors, Black Lives Matter activist and author; Alicia Garza, founder of Black Futures Lab; and Layla Saad, author of Me and White Supremacy.

As a Party leader, how did you address sexism in the organization? What advice do you have for addressing it in today’s movement work?

Sexism came into the Black Panther Party because men didn’t leave all of their socialization at the door. How’s that possible? We bring everything with us. There were men who didn’t want to take direction from women. I experienced this myself when I was the director at the Oakland Community School. A man who worked there didn’t want to take direction from me. In a moment like that, I go to curiosity rather than reaction, and I have a conversation.

Address the sexism. But not with the immediate rage or anger that you feel. Asking a question like, “How’s that work for you?” and making it a thoughtful conversation. These conversations are not one-offs, either. They are continual.

There are a lot of Black women having these conversations with Black men. What would you say to a Black woman who says, “I hear you, but the emotional labor is taxing?”

I would say that if you’re exhausted, if you are emotionally tired of having those conversations, stop. That’s the first thing I would say. Rest, don’t do it. I love this thing that I saw, once a long time ago, of geese flying in formation. As they continue to fly, the lead goose goes to the back and another one slides forward to lead. So, we can do these conversations in rotation. It doesn’t have to be the same person going back again to the same men. Gather a group of men who get it and have that fun conversation. Let them do the work.

We’re all exhausted. We also have our White friends calling us. I don’t know about you, but it was exhausting. My White friends were calling, emailing, and texting me about “What do I do?” I sent them to Showing Up for Racial Justice, which is an organization created by White people for White people to sit and talk about what it means to be White. I share this story because I think about how men need to talk to men [about addressing sexism].

“Love is a great power. Use it to transform the world.”

The Black Panther Party boasted many incredible women fighting for liberation. What was sisterhood like in the Party?

When I worked on the Party newspaper with Elaine Brown and Joan Kelly, we were the editing team. We received stories from all over the world for the Black Panther Intercommunal News Service. We decided which story would go in, then we would turn it over to the artists and the layout people. This work was three nights or maybe four—day and night, nonstop, Elaine, Joan, and I. As members of the Party, we lived right on the fringe of life continually. We became quite the sisterhood, as you called it. It was very important. We laughed a lot. That’s my memory. I mean, we worked really hard, and we are all mothers. But we would just laugh at anything that was laughable.

Your activism is a testament to “none of us are free until we’re all free.” Tell us about your work in developing programs for the LGBTQ+ community.

Let me first say there were gay, lesbian, and bisexual people in the Black Panther Party. In my experience, people were not demeaned because of their sexual orientation or preference. I don’t remember anybody caring. I had as many boyfriends as I did girlfriends in the Black Panther Party.

After the Black Panther Party, I worked in small, Black elementary schools. Then, I worked to bring mindfulness and meditation into public schools and correctional facilities. I was also a services manager at the Shanti Project in San Francisco at the height of the [HIV/AIDS] epidemic. Later, I worked at the AIDS Project. In each instance, I worked with gay men, trans people, and bisexual men, because at first that movement was all men. I was hired to not only broaden the reach to women and the understanding that needed to happen or the caring that needed to happen for trans women, but I was also asked to educate the organization about racism. That work was one of the most challenging chapters of my life because of the racism that existed at the time.

What words of motivation do you have for Black people who are doing movement work right now?

I would say what I always say: Love is a great power. Use it to transform the world.

Written By: Christina M. Tapper