Addressing “Black on Black Violence”

Addressing “Black on Black Violence”

Recently a 9-year-old Black boy, Janari Andre Ricks, was tragically shot in the Cabrini Green neighbourhood while playing in a parking lot. Janari’s death follows the deaths of six other precious young Black children in random, senseless shootings in Atlanta, Alabama, Washington, DC, Chicago, and San Francisco.

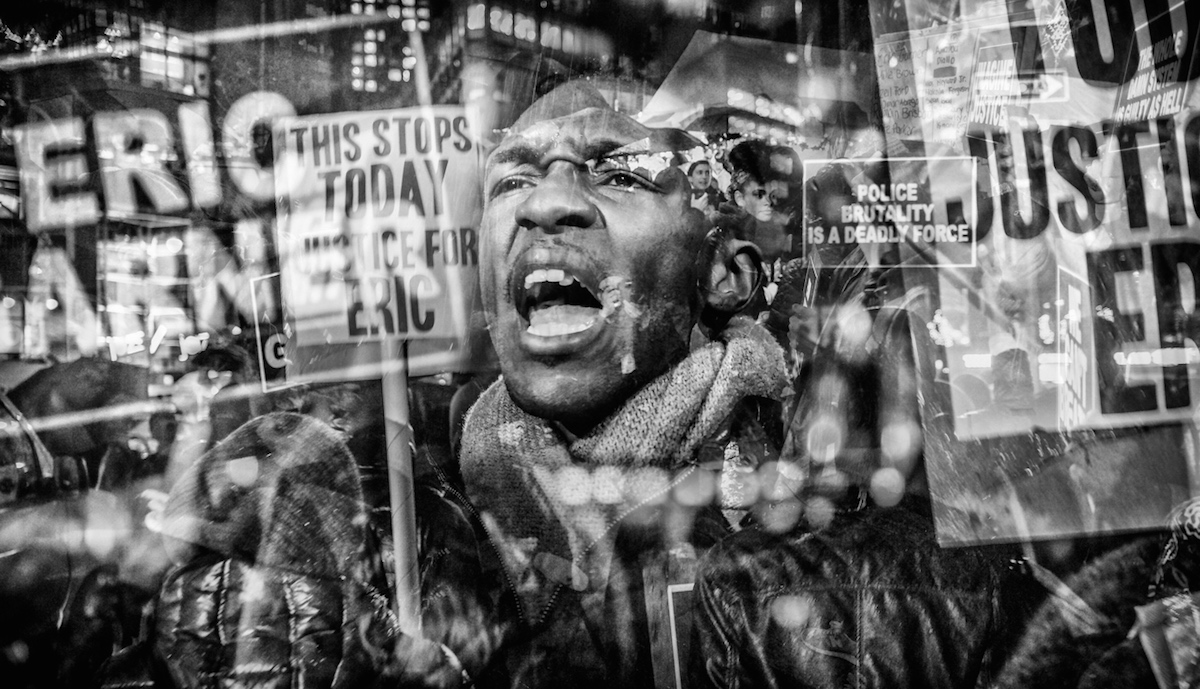

It is stories like these that have presumably led to critics bemoaning “Black on Black violence.” In my own public writing defending Black Lives Matter, a common response by critics typically references “Black on Black violence” as a way to criticise Black people who support Black Lives Matter for supposedly not addressing or caring about “Black on Black violence.”

Let me get straight to the point. I find it completely disingenuous for people to criticise Black people for not addressing or caring about “Black on Black violence” without being as passionate about addressing the social and economic factors that have created the conditions for the violence to occur.

It is a blatant prevarication (i.e., a lie, untruth, falsehood) to characterise Black people as not addressing or caring about “Black on Black violence.” The examples are frankly too numerous to mention. But let’s start with a few.

During the decades of the late ’80s and early ’90s, inner-city violence was dominating the news. The president of Morehouse School of Medicine, Louis Sullivan, organised the “Violence Initiative” which looked at how different factors such as poverty, unemployment, and the use of illicit drugs contributed to violence. Black scholars, musicians, and community activists were concerned about how to stop the violence.

In 1988, the rapper KRS-One led a Stop the Violence Movement that resulted in the song “Self-Destruction.” One of my favourite lines from the song is when Kool Moe Dee says:

“Back in the ’60s our brothas and sistas were hanged, how could you gang-bang?”

“I never ever ran from the Ku Klux Klan and I shouldn’t have to run from a Black man”

Not to be outdone, West Coast rappers followed up with the song “We’re All In the Same Gang.” Check out the lyrics from Dr. Dre and MC Ren:

“Yo, bullets flying, mothers crying, brothers dying”

“Lying in the streets, that’s why we’re trying”

“To stop it from falling apart and going to waste”

“And keeping a smile off of a white face”

Black psychologists have also been concerned about violence in the Black community. In 1990, Amos Wilson, a Black psychology professor, wrote a book called “Black-on-Black Violence.”

A revolutionary and provocative thinker, Wilson argued that Black on Black violence was the result of socio-psychological, political, and economic causes that serve to perpetuate White domination. Far from being an apologist for Black behaviour, Wilson argued that ultimately the ending of Black-on-Black violence was primarily, if not solely, the responsibility of Black people.

In 1991 Na’im Akbar, a well-known Black psychologist and proponent of Afrocentric psychology, wrote an article called “Mental Disorder Among African Americans.” In this article, he identified four categories of mental illness among African Americans, one of which he called “Self-Destructive Disorders.” He described self-destructive disorders as destructive attempts to cope with the unnatural condition of White supremacy, where individuals exhibit a survival at any cost mentality that was directed at themselves or other Black/African people.

Before people get up in arms about this, no these categories have never been recognised by mainstream Eurocentric psychology as official categories of mental illness. Insurance companies will not cover these categories for therapy. It is probably best to think of these categories as heuristics that speak to the inadequacy of Eurocentric conceptualisations of mental health when addressing the challenges facing Black communities.

As a doctoral student in the mid to late ’90s, I was concerned about violence in Black communities, along with many other academics. In 1996, I published my first article in the Journal of African American Men called “The psychological and socio-historical antecedents of violence: An africentric analysis.” I argued that the cycle of violence in Black communities was the result of American values (e.g., individualism that privileges individual rights over concerns for the group) and social inequities. In a strikingly similar article that reflected the concerns during that time, Anthony King published an article the following year in the Journal of Black Studies called “Understanding violence among young African American males: An afrocentric perspective.”

In 2015, Spike Lee addressed the issue of gun violence in his film “Chi-raq.” Criticisms of the film notwithstanding (among other things Spike was accused of misrepresenting the nature of gang culture in Chicago and perpetuating a hyper-masculine reduction of women to sexual objects), Spike was attempting to have a discussion about gun control and about saving lives.

When I received a recent email from a former White football coach telling me that Black lives do not seem to matter in the inner city, I was perturbed. Yes, the violence in inner cities is a problem, and we should do everything we can to solve the problem. But as Michael Harriot reminds us in a recent op-ed, most victims of crimes know their assailants, and data show that 83.5 percent of White victims of homicide are killed by other White people, while 90.1 percent of Black homicide victims are killed by other Black people. Yet we do not hear a narrative about “White on White violence.”

Harriot also reminds us that actually Black people do talk about Black on Black violence all of the time, as my previous examples indicate. The phrase “Black on Black violence” has become a political trope that is used reflexively to dismiss support for the Black Lives Matter movement.

In Linda James Myers’s theory of an optimal worldview, she teaches us about diunital reasoning, which encompasses a both/and perspective. In other words, we can talk about police violence against Black people and talk about violence in the Black community at the same time. That is exactly what Black people have been doing.

My hope is that we will get to the point where we are doing more than talking, and that we will act in ways that will lead to the reduction of violence in the Black community. Until that time comes, you will excuse me if your fake concern about Black on Black violence falls on deaf ears.

Written By: Kevin Cokley, Ph.D for Psychology Today