#BHM Black Victorian: The story of Queen Victoria’s Nigerian protégé

#BHM Black Victorian: The story of Queen Victoria’s Nigerian protégé

Sara ‘Aina’ Forbes Bonetta is a fascinating figure in Black British History. Most of Sara’s life is told through the voices of others. Her connection to Britain was forged in the 1840s, a time when the British Empire was at its peak. In 1848 Captain Forbes, a British naval officer, was on an anti-slavery mission in Dahomey, now Benin.

Ironically, he asked for Sara as a present to take back to the UK despite formally being against slavery. The King of Dahomey accepted this request and presented her to Forbes as a diplomatic ‘gift’ to Queen Victoria. The young girl was not up to ten years old when Forbes took custody of her in this exchange. At this point, Forbes named her Sara, adding his surname and and ‘Bonetta’, based on his ship, to the young girl’s new title. Once she arrived in the UK and visited Windsor Castle, Queen Victoria became her patron and gave her the nickname ‘Sally’.

Our black protégé had most of her story told by others. However, there is one record that reveals her courage and self-pride. Her marriage certificate describes her as ‘a negress of Dahomey’, but when asked for her full name, she gave ‘Aina’, and at that moment acknowledged the part of her tale that wasn’t British.

By revealing a name and a past that preceded Britishness, she affirmed her African identity.

This was a power move for an individual who often never had the chance to speak with her own voice. Her name identified her beyond the confines of Empire.

In the mid-1800s, the intellectual agenda of the Empire was at its height and accompanying it were racial theories rooted in anti-blackness. In the UK, Sara was not seen as human, instead being referred to as ‘property of the crown’. In Victorian Britain, blackness was perceived through a lens of inferiority. The British told tall tales of exotic lands with sub-human inhabitants, against the backdrop of a ‘colonising mission’. Scientific fixations on racial hierarchy entrenched the country in a form of discrimination which was indicative of the epoch: racism.

Around the time Sara would’ve boarded the Bonetta ship with Captain Forbes, perceptions of fixed racial identities were solidifying. Scientists like George Morton believed in a racial order, with whites as intellectually superior to non-whites. Sara’s contemporaries undoubtedly viewed her through this lens of black inferiority, with historical accounts from both Forbes and Queen Victoria offering a glimpse into the prevailing ideas of the world she was thrust into.

Captain Forbes’ diary, for instance, reveals the shock and fascination she inspired as an individual. In his Memoir, ‘Dahomey and the Dahomans’, he noted that she was ‘a perfect genius’ and had a ‘great talent for music’. Forbes’ extreme surprise at Sara’s intelligence derived from anti-black stereotypes.

He assumed she would not be intelligent because of racial narratives that assigned her a label of inadequacy.

Queen Victoria’s journal also details the ocular stir that she would’ve created in an increasingly race-conscious society. It read that she was ‘sharp and intelligent’ and fluent in English. Although she noted cognitive similarities between Sara and other (white British) children, the former’s phenotype acted as a significant means of differentiation from the white norm. ‘She was dressed as any other girl. When her bonnet was taken off her little black woolly head and big earrings gave her the true Negro type’, Victoria wrote.

This diary entry shows that Queen Victoria was intensely aware of the racialised attributes of Sara’s appearance. What’s more, the Queen’s thoughts reveal the Victorian interest in classifying the visual world and those who live in it. Reading these words today evokes an equal sense of intrigue, an intrigue mired by discomfort with the reality of blackness being read as a subject of whiteness.

It seems that Sara’s intelligence was the only point at which white Victorians appreciated her humanity.

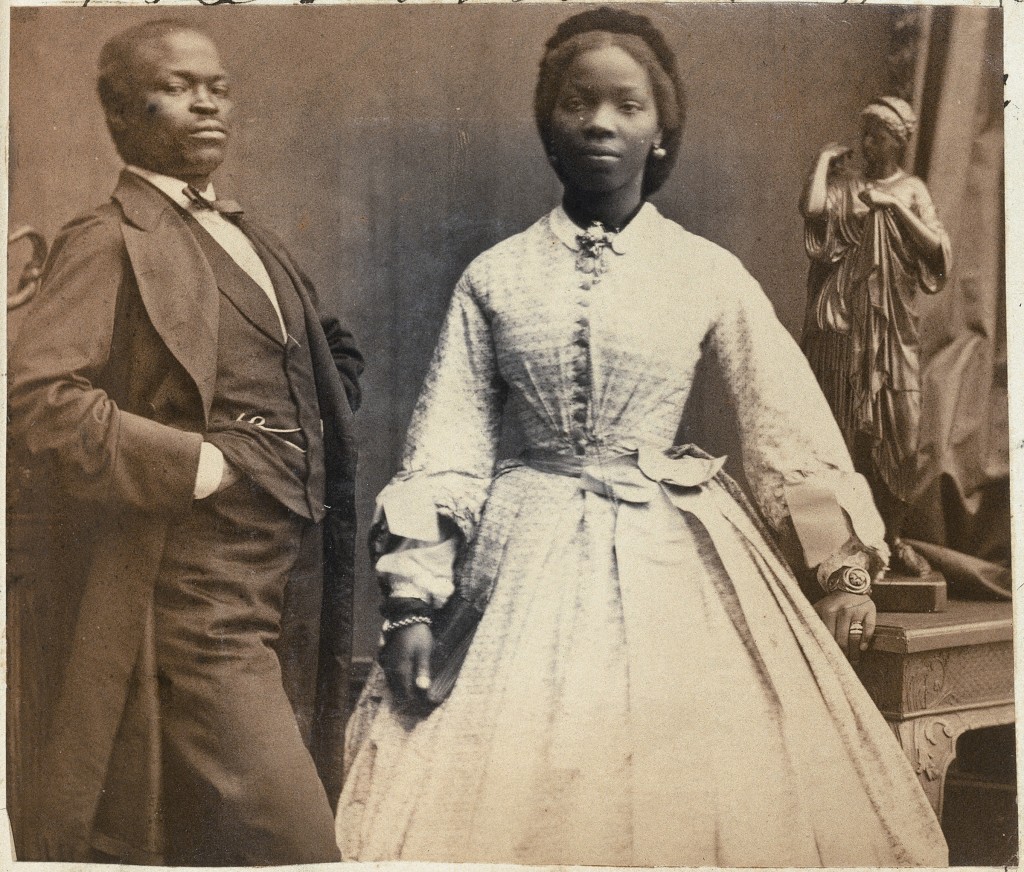

Sara’s personal life was largely influenced by English culture and interests. The gender norms in the Victorian age meant that she married very young. At the age of 19, she ended up marrying another black Victorian, His name was James Davies, and he was selected for her, due to his financial success and Christian values – making him an ideal suitor in terms of social status.

Sara was a former slave held by the King of Dahomey and Davies; her spouse was the product of liberated slaves. Together, they formed a union displaced by bondage but strengthened through imperial links to the Victorian elite in Britain. This cultural complexity gave the two of them a hybrid identity that was ahead of their time. Today, it is common for someone to feel equally West-African and British, as the African diaspora is established in the UK today. However, in the 1800s, their experience across two cultures was something extremely rare.

Overall, Sara ‘Aina’ Forbes Bonetta’s life is a captivating chronicle that inspires strong reactions. While it is tempting to paint her as a Black royal, it is clear that her story is much more complex. Sara may have benefitted from Queen Victoria’s power, but she was not a princess. Nevertheless, her story is symbolic of the Black history of Britain. A Britain where a black person held connections between two continents. Sara was a ‘third-culture kid’ centuries ahead of her time. Her resilience against racial hierarchies undoubtedly sustained her throughout her life. Her actions, small yet defiant, reveal a human dignity that transcended royalty.

Written By: Funmi Lijadu – a Nigerian-based collage artist and writer. In her work, she enjoys exploring her identity as well as wider socio-political issues she observes in the spaces she’s in. Blog and portfolio: funmilijadu.com Instagram: @artbyfunmi

Header Image: Queen Victoria’s goddaughter Sarah Forbes Bonetta with her husband James Davies on her wedding day (Getty)