“Black Is King” Navigates African Cultures and the Diaspora’s Imagination

“Black Is King” Navigates African Cultures and the Diaspora’s Imagination

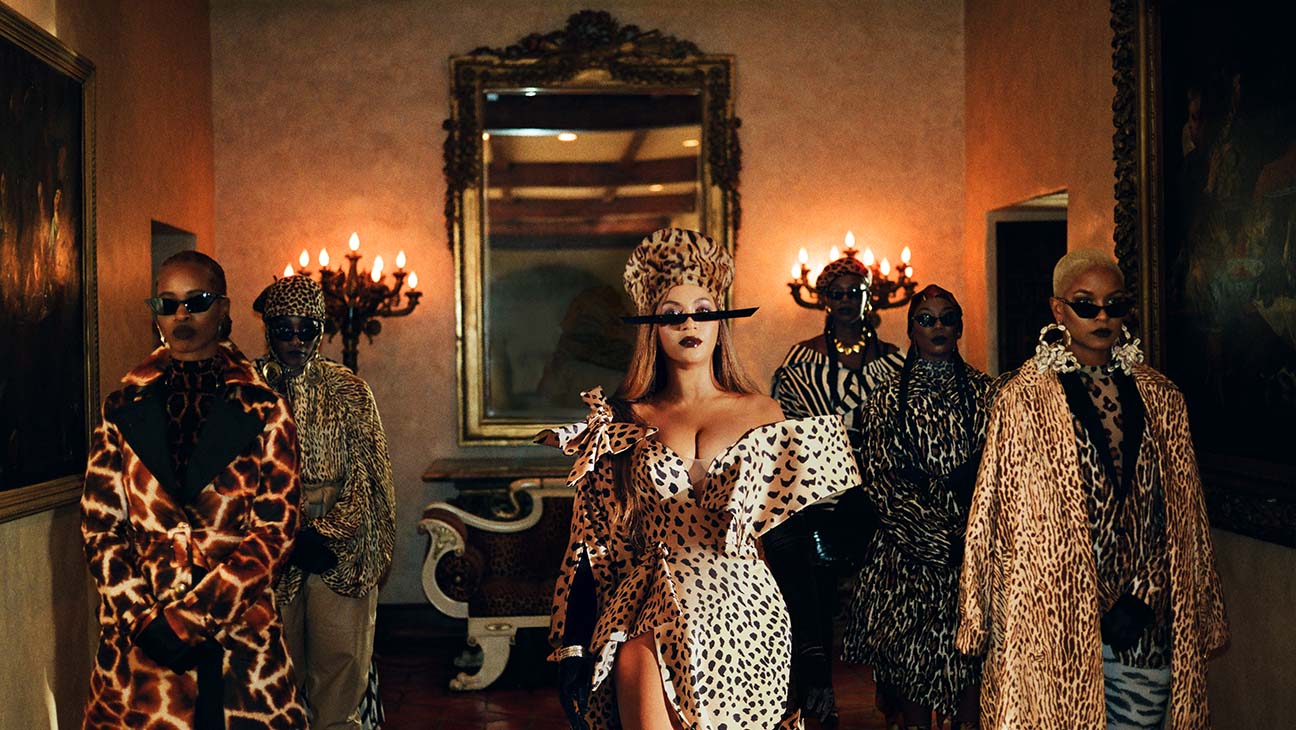

From a purely artistic point of view, it would not be hyperbole to regard Black is King as one of the most visually exquisite projects to come from the American pop culture landscape in the digital music era. Beyoncé’s latest self-written, self-directed visual album demonstrates both a consistent commitment to resurrecting video’s relevance in the internet age, and reminds music lovers that her artistry will always extend beyond her vocals. In Black is King, images and storytelling reboot the musician’s curated album, The Lion King: The Gift to accompany a retelling of the beloved movie’s 2019 photorealistic animated remake. But it’s also Beyoncé’s love letter to a multitude of cultures on the continent and in the African/Black diaspora alongside artists, musicians, and dancers of various African spaces. Or, at least, that’s what Black is King attempts to be, even where it falls short.

The film brims with influence, inspiration, and a slew of cultural expressions. There’s the stunning green gele, a renowned head tie originating in Yoruba culture but adorned today by West African Nigerians, Togolese, and Beninese; the Lipombo-inspired hairdo of DR Congo’s Mangbetu ethnic group; and the cowhide fashions influenced by Southern Africa’s Xhosa, Ndebele, and Zulu peoples, who have a long history of making use of Nguni cattle for clothing and weaponry. There’s the Adumu dance of Maasai warriors who reside in Kenya and Tanzania, and Nigeria’s popular Zanku dance (created by Nigerian musician Zlatan and taught to Beyoncé by Stephen “Papi” Ojo). There’s Ghana’s dancehall king, Shatta Wale; South Africa’s “future ghetto punk” inventor, Moonchild Sanelly; and Nigeria’s Afropop queen, Yemi Alade. Altogether, Black is King synthesises long-standing cultural forms and ensembles with contemporary pop culture phenomena to create an imagined world of blended African cultures living alongside one another, distinct perhaps only to those who can identify and distinguish them.

Not surprisingly, the film has prompted a discourse about how the West looks at and represents the African continent. The most obvious critique is that the visual illustration of African cultures seamlessly blending and merging, with Beyoncé at the center of it all, results in a hodgepodge of cultural appropriation and Africa’s hegemonization—the latter of which has long been a predictably Western and specifically American perception of a continent that consists of 54 countries and at least 3,000 ethnic groups. But the narrowness of this view is underscored when we consider Black is King as a product of living, dynamic African cultures that were in conversation long before European conquest, and that remain both in proximity to and separate from, each other. Moreover, taking such a view ignores that Beyoncé herself belongs to the Black/African diaspora as well, and is entitled to at least some of its stories, its cultures, its art—and its imagination.

The boundaries of the African/Black diaspora’s claim to the continent’s history and culture is a conversation worth pursuing, and Black is King may or may not be the best entry point for that pursuit.

At the heart of such a conversation is a question of belonging: To whom does Africa belong? To whom does its diaspora belong? And if there are differences in belonging, who is allowed to claim and participate in cultures they are simultaneously close to but far removed from?

The film may not have these answers, but it might compel viewers to reckon with the history of what we might call Africanness, and how it was transformed definitively into Blackness in the so-called New World. Black Americans aren’t to blame for their expressions of blended African culture; history makes this inevitable. Perhaps then, Black is King is less an offensive hodgepodge of African ethnic groups but instead, a bewitching amalgamation.

“None of the Africas the rest of the world imagines are any of the ones that Africans think and live and work and die in,” as Boluwatife Akinro and Joshua Segun-Lean wrote last year in their critique of The Lion King: The Gift. Some of these imaginations even include an Afrocentrism adopted by Black Americans that distorts African histories, constructing forebears as avatars of aristocracy. Certainly African history includes kingdoms, but surely if there were kings and queens, there were also subjects. And if the past is distorted, then so is the present, and superfluous histories are formed to affirm present yearnings to be seen as worthy. It’s a similar and necessary sentiment to the one Nigerian literary giant Chinua Achebe wrote in The Education of a British-Protected Child, cited in the piece: “…I do not believe that black people should invent a great fictitious past in order to justify their human existence and dignity today.”

Yet even where Beyoncé employs the language and exhibition of royalty—on one hand to showcase what many Africans can concede is the ostentatiousness of celebration in ceremony, or on the other, to elevate the humanity of African peoples via expressions of abundance—she does so in the tradition of the Black American sentiment that was forged to restore humanity to ancestors from whom it was violently separated. Indeed, neither people from the continent nor the diaspora require wealth or vestigial royalty to claim they or their ancestors’ humanity, though such expression in the film is forgivable—The Lion King, after all, is a tale about the son of a king, Simba, and his return to reclaim a kingdom. Still, what is to be critiqued in Black is King in its human representation of Simba, the romance of a boy who must remember who he is to survive the tragedies of life, and subsequently, thrive, is also what is to be praised.

Despite the sometimes disjointed stories in Black is King’s retelling—another critique—this reproduction of African cultures comprising old and new, traditional and modern, the imagined civilizations of ancestors, the palpable presence of the many ways to be African, within the continent and outside it, always exists with these conflicts. The being is in the contradictions. From the perspective of more than art, from a diaspora that inevitably regards the continent as a home of many places only knowable in displaced memory, Black is King works because it is honest: a film of hope and belonging, represented by those whose cultures and diaspora continue to survive and thrive beyond a displacement that is similar, but not the same.

Written By: KOVIE BIAKOLO

Kovie Biakolo is a writer, editor, and multiculturalism scholar specialising in culture and identity.