Education: A Double-Edged Sword

Education: A Double-Edged Sword

We typically conceive traditional systems of education as liberating forces, especially in the context of black African women. Triply marginalised through race, nationality and gender, schooling often poses as pivotal to our socio-economic advancement.

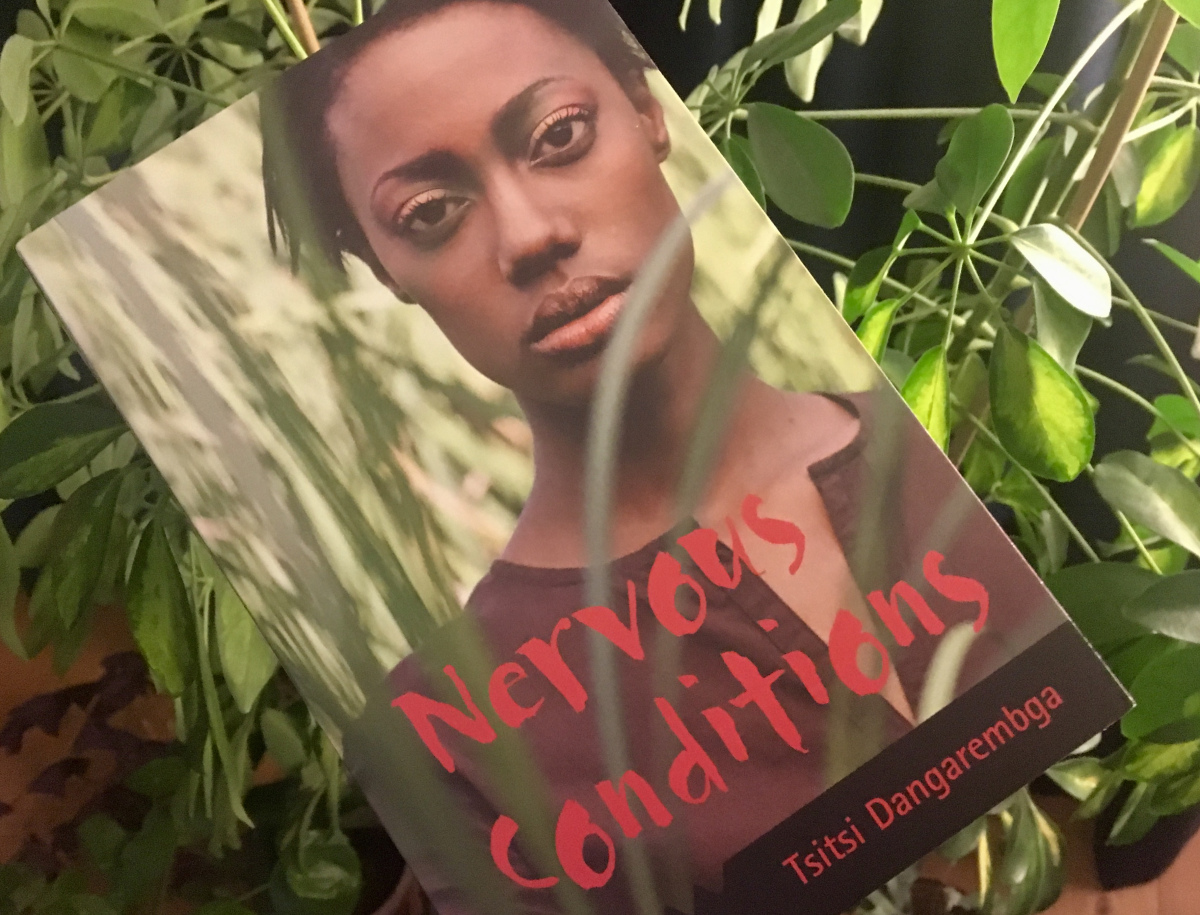

But while quantitative data presents the benefits of such exposure as absolute, Tsitsi Dangarembga considers the troubling history of certain forms of education. In the process, she exposes the psychological implications and the cultural limitations for African women in a 1960s – early 1970s Zimbabwe. In her award-winning novel, Nervous Conditions, the concept of formal schooling is imagined within a colonial framework. Education in this context, thus, takes on a structure that is steeped in white social and cultural ideals, imported from Europe by the dominant settler community and the educated ‘native elites’ who stand proxy.

There are so many characters and avenues in which the book details this phenomenon, but the figure who resonated with me the most in this novel was that of Nyasha. As a recently returned migrant child, Nyasha typifies this condition. After spending five years in England during the formative period of her life, she returns to Zimbabwe, her home country, barely able to speak her native language of Shona. During the family reunion, her mother, Maiguru, laments that Nyasha and her brother, Chido, “have been speaking nothing but English for so long that most of their Shona has gone.” This alludes to a language barrier dividing Nyasha and her brother from the rest of their family.

Though initially subtle, Nyasha’s state of twin nationhood causes increasingly more psychological and physical trauma for the character as the story progresses. Notably, the same cannot be said for her brother, who appears to fluctuate between the two cultures almost seamlessly. Over the course of the book, for example, we see the young girl develop an eating disorder, first in the form of bulimia and then anorexia. What begins as mild instances of Nyasha picking at her food ends in a full-blown mental and physical crisis (after a fainting episode), where she finds herself under the inspection of a white psychiatrist in Salisbury. In the journey to Nyasha’s breakdown, we witness the harmful ramifications of an imported value system which disproportionately governs women. Accordingly, consumption defines resistance and compliance, with the young girl taking the path of resistance as she pursues a thin ideal which opposes the typical preferences of plumpness, held by her community.

In the wake of this crisis, the frank warning that “the Englishness [will] kill them all if they aren’t careful”, from Nyasha’s poor and illiterate aunt, Mainini, underpins the possibility of danger via the cultural disassociation that comes as a result of engaging with these systems of whiteness – especially for African women. Indeed, though Nyasha is materially privileged by her exposure to English teaching, enjoying a wealth of financial and social resources that prove inaccessible for the majority of Zimbabwean women in the novel, it comes at the expense of her mental health. Furthermore, her interpersonal relationships with members of her community are also impaired, which works to compound her distress. Nyasha’s level of education places her in constant and sometimes violent conflict with her father, Babamukuru. This culture clash is most visibly seen when he hits his daughter over fears of her chastity when she is caught late at night talking to a white boy, labelling her ‘a whore’. The gender divisions in this hybrid national existence become abundantly clear when we realise that Chido, who also schooled in England, never faces such harm.

Furthermore, the line between active and inactive defiance, in the case of Nyasha, proves decidedly blurred. Dangarembga uses this confusion to mirror the disparity between the family patriarch’s condemnation of his daughter’s behaviour as disobedience, and Nyasha’s headstrong mentality, after being immersed in changing value systems which have given women greater civil liberties.

Emancipation, therefore, comes with social consequences and cultural pushback for the women who challenge these orthodoxies. In real-world terms, we see this evidenced across the global South, where a large proportion of women remain uneducated by design. Rwanda, for example, often tops the global gender equity tables, yet critics have called this a ‘gender front’ in which women are superficially enfranchised but usually denied any true power. Despite women having 61.3% representation in parliament, the majority of these female ministers have very little influence policies concerning women, such as maternity leave which remains at just twelve weeks for new mothers. Moreover, businesswoman and politician Diane Rwigara, who was educated in the US, faced formal accusation of inciting insurrection and had alleged nude photos leaked, during her rival campaign to Kagame during the 2017 presidential election. These actions formed a blatant and institutionalised plot to suppress her opposition, highlighting the social ramifications for some educated women in the continent who dare to seek more agency than allocated.

Coming to the UK at the age of two, from Nigeria, and being socialised as British outside of the home but as Nigerian indoors, reading Nyasha’s story reminded me of some of the periods of cultural isolation I experienced as a child. Though not equivocal by any means, upon moving from a relatively diverse city (Manchester) to an uncomfortably white space (Newcastle) at the age at 12, I was desperate to attend the only school a substantial number of black students in the region. I wanted to be among my peers, though my parents forced me to attend a predominantly white school which far outperformed the former failing institution. Arguably, I materially benefited from the experience. My dad had moved us for the sake of a new job, thus, granting us more financial stability and I probably achieved better academic results than I would have at a place that lacked the necessary resources to facilitate this. Yet, culturally and socially, I was left relatively destitute, isolated from anyone that looked like me beyond my immediate family and the few dispersed black faces within the school. My participation in this system, and British culture generally, also led to conflict between me and my parents over moral perspectives which often stood diametrically opposed to one another.

Ultimately, Dangarembga’s Nervous Conditions forces us to confront the limitations of the so-called ‘educating’ mission constructed by European powers.

The events of the story showcase that, qualitatively, many barriers continue to impede the development of marginalised women, both within white hegemonic rule and African forms of patriarchy. Contrasting characters throughout the novel, and in the sequels, The Book of Not and The Mournable Body serve to highlight this western arrogance by further demonstrating the ramifications of imported pedagogy, amidst alien political rule.

Written By: Hannah – an award-winning writer who is passionate about discussions centring black women and the nuances within this identity. Connect with her on Instagram and on her blog.

Header Image: courtesy of Africa Global Radio