Running (from) home

Running (from) home

“Where did all the Black people go?”

When Aunt Hanan visited Nuremberg in 2012, she noticed that there were no Black people on the streets. The 90s Bavaria she remembered had been full of African-American soldiers who had brought “style, good music and money”. When they left, Black Germans were rendered an invisible minority, still figuring out who they were. According to my aunt, we had failed (we neither had style, nor good music, nor money). The hyphen within Afro-German had manifested into a clear break between two opposing identities: Afro | German.

My African-Arab father and white mother raised me in conservative Southern Germany. Black diasporic womanhood was a foreign identity to all of us. We had no education on Afro | German history, literature or presence. In 2012, at 15, I felt that Germany was no place for someone like me and moved to England. It is common for Black Germans to explore the skin we inhabit abroad. We look to America, the UK and France, fascinated by their Black diasporic communities. These countries present a positive kind of Blackness, the type that is stylish because it was birthed outside of Germany. I longed for London’s Black safe spaces where English allowed me to voice what German refused to understand. There, the hyphen became a compromise: Afro-German, horizontal independence and biannual loss.

Every June and December, I left my Black business at Germany’s borders where it patiently waited for me to return on my way out.

In 2020, after five years abroad, the pandemic catapulted me into my mother’s flat in Nuremberg. As I read about the disproportionate threat of COVID-19 on Black communities, I was alone with my worries about doctors’ biases towards Black people. Asking myself “What does it mean to be Black German in a pandemic?” required my Black business to finally cross the hyphenated border. The possibility of catching corona ended years of carefully compartmentalising my Self. I turned to books and the internet. Looking back, it seems ridiculous how surprised I was to find a world of organising, literature and film that had been documenting Black German identity and history for decades. Afro-Germany had existed long before Aunt Hanan’s African-American Bavaria.

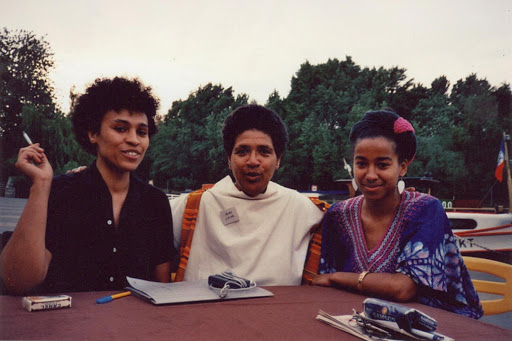

The term Afro-German was coined by a group of women around the poets, educators and activists Audre Lorde and May Ayim. Alongside Katharina Oguntuye and Dagmar Schultze, Ayim co-authored the first Afro-German book Showing Our Colours: Afro-German Women Speak Out (1986). They traced African-German histories and collected the first published testimonials of Black German women living in a Fatherland that constantly questioned their right to belong. In the documentary “Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years 1984 – 1992”, Schultze shows how Lorde’s presence in Berlin gave rise to the New Black Movement. For the first time, Black German women came together and explored the possibilities of community and intersectional activism through language and knowledge production. They founded the Initiative of Black People in Germany (ISD) during the 1990s, hoping to create a future in which Black Germans would no longer have to justify their existence or explain their lived realities to an ignorant white majority.

Three decades later, we have not yet arrived in the future they envisioned. In 2019, African-American-German journalist Alice Hasters published “Was weisse Menschen nicht über Rassismus hören wollen” (What White People don’t want to Hear about Racism), a currently best-selling account of the challenges and everyday discrimination against Black women in German society. She writes that growing up, she had no idea that other Black German women were discussing the very same topics. Neither did I. Black German conversations never left the niche in which they were forced, until Alice Hasters’ book about my lived experiences became a bestseller. Her literary achievement compounded the political victory for Aminata Touré who became the youngest and first Afro-German woman vice president of a county parliament in 2019.

Black Germans have b-e-e-n creating mirrors for our lived experiences, even though we were not raised with a sense of collectivity or a unifying self-identification. We are having these conversations now and openly. Audre Lorde’s and May Ayim’s legacies gave name to Afro-Germany, a term I have claimed ever since Lorde said that hyphenated people are the “last chance for Europe to learn how to deal with difference creatively”. Understanding myself as a hopeful possibility, even a necessity, for European society is the most self-affirming identity I can give myself. At 24, I am beginning to explore the symbolic power of my hyphen.

“borderless and brazen: a poem against the German “ u-not y.”

i will be African

even if you want me to be german

and i will be german

even if my blackness does not suit you

i will go

yet another step further to the farthest edge

where my sisters – where my brothers stand

where

o u r

FREEDOM

begins

i will go

yet another step further and another step

and will return

when i want and remain borderless and brazen

May Ayim, 1990

Written By: Amuna Wagnner – a German-Sudanese writer living in between Cairo, Nuremberg and London. On her blog Kandaka she explores creative activisms and radical healing through art (www.kandaka.blog). Her writing locates personal stories within bigger contexts and revolves around the themes of gender, heritage and decolonisation. Follow her on Instagram

Header Image: Photo of Katharina Oguntuye, Audre Lorde and May Ayim at the House of the Cultures of the World (1988) Dagmar Schultz