“That’s still a thing?!”: Food Deserts and Black America

“That’s still a thing?!”: Food Deserts and Black America

While the pandemic rages on, other infrastructural issues in the United States persist, quietly devastating historically neglected low-income communities. Beyond the well-understood physical and mental impact of COVID-19, such as social isolation and deadly symptoms, 42 million people potentially experienced food insecurity due to the pandemic.

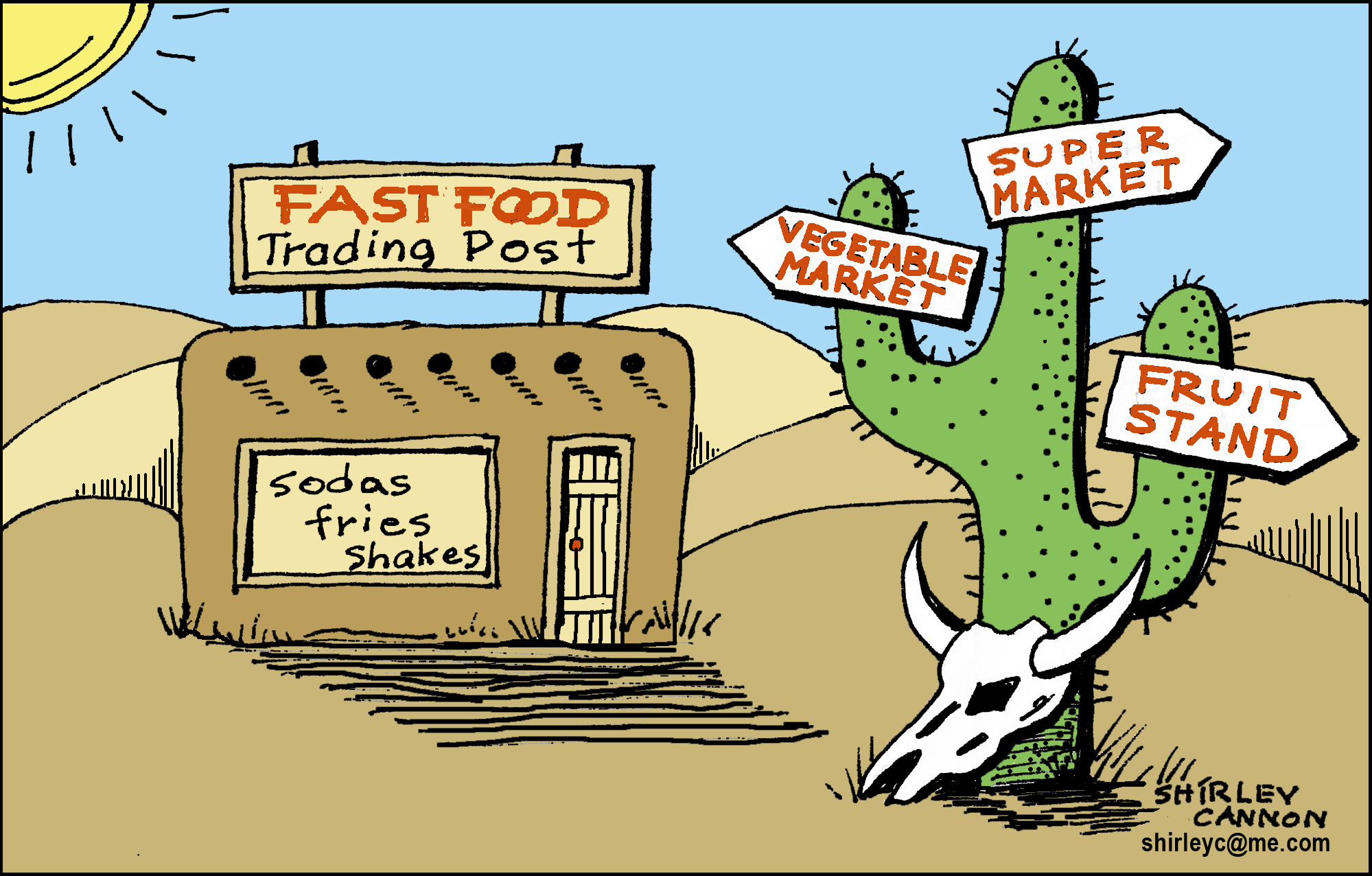

Food deserts are a facet of food insecurity that has plagued this nation since the 1970s and beyond – an issue that COVID-19 has further exacerbated. A food desert refers to a place where inhabitants lack consistent access to affordable and healthy foods. Without the ability to easily shop at a nearby grocery store with quality produce, people are usually limited to fast-food chains and corner stores for nourishment. In the long term, folks living in these areas can suffer from health issues such as diabetes or heart disease. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, about 39 million people lived in such regions in 2015. I spoke with Alabama native Christopher Neal about his lived experience in a food desert and how various Women in his life informed his diet.

“I remember it being so rare that I went to a grocery store that we actually took a field trip there”

When did you experience a food desert?

“Quite honestly, up until recently. Adulthood. I remember growing up, there was a lot of fast food: Hot Pockets; I remember ground beef; I remember walks to McDonald’s. I’ve heard my mom say that meals were composed of the most filling combination of foods. Hardly ever did vegetables fall into that category. My mom wasn’t the biggest cook. We had home-cooked meals, but I can’t recall seeing any fresh vegetables on the table, and if we did, it was from a can. My grandmother cooks real foods, real veggies, but that was a weekend thing. We rarely got to see these meals being prepared.

I remember it being so rare that I went to a grocery store that we actually took a field trip there. We took a field trip to the grocery store because that’s where you could get actual food, not Hot Pockets and Lunchables. My first time eating a pineapple was on this field trip. I had never had a pineapple. I was ten years old. My first time tasting a mango was three years ago. And I’m thirty. The first time I saw an avocado was in college.

Now, I don’t buy any processed food if I can avoid it, but it took a long time for me to be food conscious. Dr Chandlers, my college professor, made being an informed consumer a major part of our curriculum. She introduced me to the study of plant-based diets and how to reverse the effects of cancer and cardiac diseases. If I hadn’t gone to college, I would have never gotten that introduction.

It’s almost impossible for someone who grows up in poverty to have that information or to have that access. I have brothers, cousins…. we all grew up in the same area and where you stayed determined what type of food you ate. That’s still relevant to this day. The house we just moved from, I couldn’t tell you where the grocery store was over there. We currently live less than five minutes from where we stayed previously, and just that change in zip code provided us with a variety of stores to go to.

Food Dessert Graphic by Jo Ramos

Why is that? What’s the difference between those two areas?

There’s a big difference in demographics. Here, we’re seen as a college area because we’re near the sister school to Dillard University. The area we moved to is also historic, so it has the “backing” of our local institution. We are the only Black people on our street: the only and the youngest. We moved in [sic] June 1st last year, after George Floyd’s murder.

Where we were before, our neighbours were white, but they weren’t upper-class. They were middle to poor whites. More poor than anything because there was a lot of rent. We all know that gerrymandering is a form of racial oppression, but in this case, I can’t say it’s directly racial because my neighbours then were also white. Classism is a better reflection.

How can food desert communities overcome these barriers?

I think you have to first help people out of their survival mentality. Getting people to realise: “Hey, you’re in survival mode right now. You’re doing what you can to get by. That’s not the same as living.” Whatever that entails. I don’t know how you do that. If someone is trying to feed their kids, there’s nothing you can tell them — I’m a father — there’s nothing you can tell a parent who’s trying to feed their kids. I don’t care how you put it, how detrimental it is to the health, welfare, and benefit to everybody in the community. An infusion of wealth can be a way to get people out of that mentality.

How do you think living in a food desert affects people’s perception of food in general?

For one, it affects your palate. I also honestly think it limits your perspective of the world, how you see foods from other cultures, and how you view people from these cultures. The first time I went with my cousin to Mexico, I was terrified to try the food, and it tasted horrible, but I stuck to it. I kept trying it. Exposure therapy is the most amazing thing. You scared of some shit? Just go up to it. Just do it. And it works! You try food. Start small. Start with vegetables. Try different organic vegetables. An exposure to a different variety of foods.

For almost ten years, me and my friend [sic] have had this joke whenever one of us goes grocery shopping. We’ll take a picture of the full fridge and we’ll text each other and say: “Options”. We do this to this day. The premise of the joke is [that] we never had options. Ten years later, it’s still funny. Just seeing vegetables in the house changed our outlook – small, small things like that.

Written By: Akhir Ali (she/her) – a writer from Washington D.C. who writes fiction, personal essays, and queer erotica. Her work centers contradiction, disembodiment, natural environments, and intimacy. Check her out on Instagram