#BHM Olive Morris: the Unapologetically Black Radical Squatter

#BHM Olive Morris: the Unapologetically Black Radical Squatter

42 years after Morris’ death, we delve into her acts of resistance and how her legacy has influenced modern-day Black squatters

As you walk onto the street, you move into a portal crafted by the culture of the West Indies. Jerk chicken is burning on the grill, offsetting sweet, charcoaled fumes; the rudebois are stomping on the pavement donned in their braces, long-line jackets and Rasta hats; the pulsations from nearby sounds systems are vibrating the ground beneath you with the latest fresh-presses from Kingston, Jamaica. This is home. This is ours. This is Brixton’s Railton Road in 1970s Britain. Suddenly, you turn up to a house with a plaque reading “121”. You’ve made it, you’re at the door of one of Brixton’s most radical Black squats, and behind the door stands Olive Morris.

Olive Morris was a Black radical feminist organiser who arrived in the UK from Jamaica in 1961 as part of the Windrush Generation. She was nine when she came with her family, hoping for a life with more opportunity on the land with the “gold-paved streets”. What she was met with was a facade hiding nothing but bleakness – institutional racism, sexism and an economic system that squeezed any real comfortability from the working class to feed to the glutinous few. Welcome to England.

Photograph of Olive Morris (left) and members of British and American Black Panthers. Credit: Lambeth Borough Council, Photos Archive.

It was in this bed of rocks that radical movements sprung up, and radical people took to action to fight against the deeply entrenched injustices that were pummelling people’s daily lives, especially newly arrived African-Caribbean people. Olive Morris was one of those that felt the anger of being dropped into another sunken place. She was 17 when she retaliated against a racist police attack on a Nigerian diplomat who had been accused of stealing the car he was driving. This led to her being arrested and assaulted by officers, leaving her with injuries so severe that her own brother could not recognise her face. Accounts of the incident discuss how her queer; gender non-conforming look compounded the brutality she faced from the police.

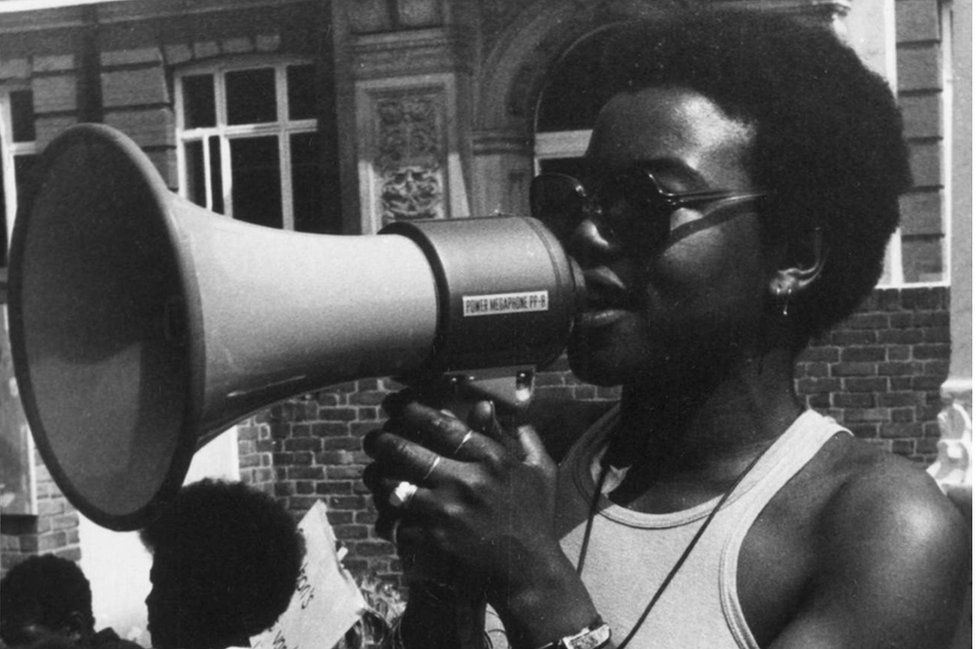

Photograph of Olive Morris confronting police. Credit: Olive Elaine 1952-1979 (libcom.org)

The chapter “Olive Morris and Sexualised Police Brutality” from the book The Other Special Relationship: Race, Rights, and Riots in Britain and the United States details this:

“Her lit cigarette, bare feet, and androgynous clothing communicated a youthful irreverence that transgressed what many perceived as the respectable boundaries of black womanhood [and] [this] violent encounter with London police officers is an example of how deeply intertwined notions of queerness, blackness, soul, and criminality were in the minds of law enforcement in the late 1960s.”

Olive Morris dedicated her life to fighting against the conditions that caused this state violence, becoming a member of the British Black Panthers. She also co-founded OWAAD (Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent) and the Brixton Black Women’s Group. All these groups focused on grassroots organising within the Black community, mostly through a socialist framework. On top of this, she was a key figure in the squatting movement, arguably becoming the most well-known Black radical squatter to date. This led her to opening the legendary 121 Railton Road squat in Brixton with her friend Liz Obi.

Photograph of Olive Morris (right) and Liz Obi (left), 1973. Credit Neil Kinlock ©

Squatting was commonplace in Black communities following the post-WW2 migration of African-Caribbean people to the UK. Racist housing discrimination made it that Black families were thrown into tightly-cramped, dilapidated housing and were not granted the same safety nets as white people. For example, mortgages were much more difficult to acquire, and Black people were pushed to the back of council housing waiting lists. From a desperation to be adequately sheltered, many Black people turned to squatting. Brixton became the hub for squatters, with many using it to radically organise through the repurposing of empty spaces.

Front cover of the Squatters’ Handbook 1979, featuring Olive Morris, published by the Advisory Service for Squatters. Credit: Lambeth Borough Council, Photos Archive.

121 Railton Road was a privately-owned flat first occupied by Liz and Olive in 1973 after they found themselves with nowhere to stay and no money to pay rent. Within the building, the two women set up Sabaar, one of Brixton’s first Black radical bookshops. They also used it as a space for Black radicals to meet and for the community to seek advice. After that, it got taken up by (white) anarchist groups, feminist groups and queer groups. The building survived as a space for radical development until 1999.

Photograph from 1973 showing Olive Morris confronting a Property Agent. Credit: Libcom.org

Olive Morris was unrelenting as a squatter. She fearlessly fought against bailiffs and the police and unapologetically demanded freedom. She is described as turning squatting into an art form. Gail Lewis, a Black British author and fellow co-founder of OWAAD, describes:

“Olive in fact got the Sabarr bookshop, the original one we had at the end of Railton Road, by going out as a part of the collective and claiming the building. In fact, when the council was going to evict them, she went up onto the roof and said, “I won’t come down until you let us have the building.””

Indeed, she was the very symbol of Black, feminist, and capitalist resistance. She continued to fight against the chains that had ensnared her and her community right up until 1979 when she sadly passed away because of blood cancer (non-Hodgkin lymphoma) at the age of 27.

Image from Memoirs of a Londoner: Olive Morris – Rambling London Tours; photograph of Olive Morris, taken by Neil Kinlock in 1973

Despite her short life, the legacy of Olive Morris remains powerful within the Brixton community, the Black radical scene, the feminist scene, and the squatting movement. In 1986, an important Lambeth council building was named after her, following the 1986 Brixton riots (although, it has since been demolished after it was kept empty for years through building security – irony?); in 2011, the Olive Morris memorial award was launched to give bursaries to young Black women; in 2015, she was chosen to be put on the Brixton pound (a currency to encourage local trade); in 2020, she was recognised in a Google Doodle. Another evident influence that can be seen is from the young radical Black squatting group House of Shango, who have repeatedly stated Olive Morris as an inspiration.

As you walk down Railton Road today, you walk past the buildings that once breathed life for the African-Caribbean community and get disheartened at the lack of vibrancy of the once culturally rich area. The building, which was once a radical Black squat at 121, has now become a colourless residential space, aching from the gentrification that has since washed away its Black revolutionary past. Do the people who live there now even know the legacy of Olive Morris? Do they feel the mighty power of Brixton’s frontline? Do they see the spirit of a Black woman stomping on their grounds and scaling up their buildings? Because Olive Morris lives on.

Written By: Lisa Insansa Woods – a journalist, writer, poet and documentary filmmaker with a degree in BA Journalism. She is passionate about feminist, anti-classist and environmentalist struggles. Check out more of her writing here

Header Image: Olive Morris. Credit: Lambeth Archives