Blessing Olusegun: The world does not stop moving for the death of a Black Woman

Blessing Olusegun: The world does not stop moving for the death of a Black Woman

Ayan Artan 06 April 21

Sarah Everard’s murder triggered something in the psyche of women across the country. With her story plastered across newspapers and her disappearance detailed on our social media timelines, we all monitored for breakthroughs in her case and prayed that she defied odds, that the unthinkable did not happen. But it did. I saw myself in her, due to her proactive sensibility when it came to her safety. Her case was undoubtedly familiar to any woman who dares to live her life fully in a male-oriented world. It shook me to the core. Discussions around the case had even seeped into my university campus, with conversations questioning how safe the spaces are we expect women to occupy.

Her murder did not just set alight public consciousness, it also confirmed every woman’s worst fear: that no matter how careful you are, no matter what you wear or how well regulated your behaviour is, the sad reality is that you may not make it home.

Caption: Tributes to Sarah Everard, Clapham Common, London. Credit: Tatiana Livesey

As Sarah’s family watched on as she received outpouring of love and solidarity across the country after death, memorialised as the embodiment of an entire gender’s struggle for safety in Britain. Blessing Olusegun’s family are forced to live their lives with the knowledge that the world does not stop moving for the death of a Black woman. Blessing was on a university work placement at a care home in Bexhill, East Sussex. Only twenty-one years old when her body was discovered on a beach a short walk from her accommodation last year, Blessing’s death was simply deemed as ‘unexplained’ by police.

Sadly, the lack of justice for Blessing Olusegun is not an isolated case for Black Women experiencing violence. In June 2020, Nicole Smallman and Bibaa Henry, two sisters found murdered in a park in north-west London after celebrating Biba’s birthday. Their mother Mina Smallman said in response to the lack of media coverage and police presence surrounding her daughter’s case that ‘other people have more kudos in this world than people of colour.’

The two women’s’ bodies were discovered by a family member in Fryent County Park, London.

According to the Office of National Statistics, a woman is murdered every 3 days in the UK and Black people make up 14% of homicide victims, despite only comprising 3% of the population. Unfortunately, there is currently no data to show how many Black Women are murder victims, a further indication of the double erasure Black Women face.

Photo Credit: Lush Brighton

In contrast to Sarah’s murder, people did not cry out Blessing’s name on the streets, and there were no vigils or marches, or hashtags organised to mourn her loss. Their deaths did not appall mainstream Britain enough for a movement to be built around her, nor did it move news editors enough for her story to grab the nation’s hearts.

And it was this, the blatant difference in the way that these two women were treated, even in death, that triggered within me one of the most critical reflections on my own positions politically as a feminist, setting my blackness and my femininity- these two intersecting parts of my identity against one another.

Being a Black Woman means that your treatment as a woman is irrevocably and intrinsically linked to your race. Your treatment is deeply dependent on your proximity to whiteness.

As the images of the protests following Sarah’s death started to circulate, we saw familiar symbols of protest adopted. #SayHerName was trending, with protesters holding signs that read “No Justice, No Peace” whilst raising closed fists in the air. These were symbols of Black protest, utilised by white women to compare strife and pain to movements like Black Lives Matter. Now claimed by whiteness, these symbols hold a different meaning, serving instead as a reminder of the entitlement that white feminists feel to having their experiences legitimised, as they simultaneously refuse to acknowledge the pain of any women that strays from their ideals of Eurocentric norms.

It is this knowledge that divides my heart on not how I feel about Sarah Everard’s murder, but on the subsequent movement she has inspired. I share the anger that a lot of white women feel. I am frustrated at the small cohort of men who defensively and unintelligently argue that the suspect’s actions were removed from the systems that oppress women.

However, if white women can understand that oppression has many faces and nuances when it comes to the female struggle. Why is it so difficult to accept that the same can be true when talking about the Black female struggle, firmly in the crosshairs of at least both racial and gendered oppression? Why do we still have to write think pieces for not only mainstream feminism but the world, to recognise the value of lives like Blessing’s?

Written By: Ayan Artan is a Somali-born, Leicester-bred pop culture, politics, and culture writer. Her work focuses on critically engaging with intersectional viewpoints, exploring topics such as race, feminine identity and the migrant experience.

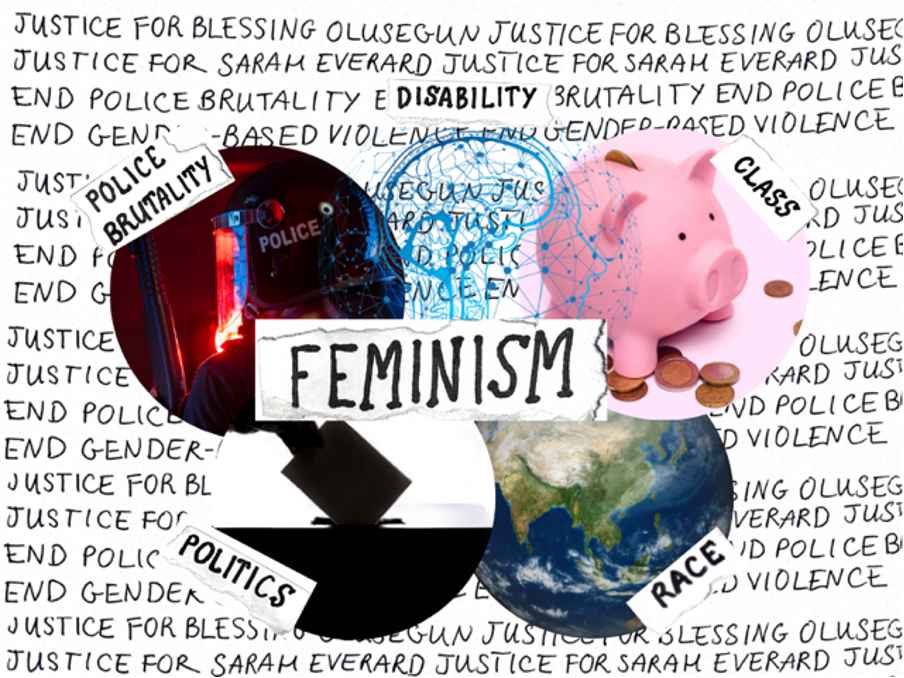

Header Image: @artbyfunmi