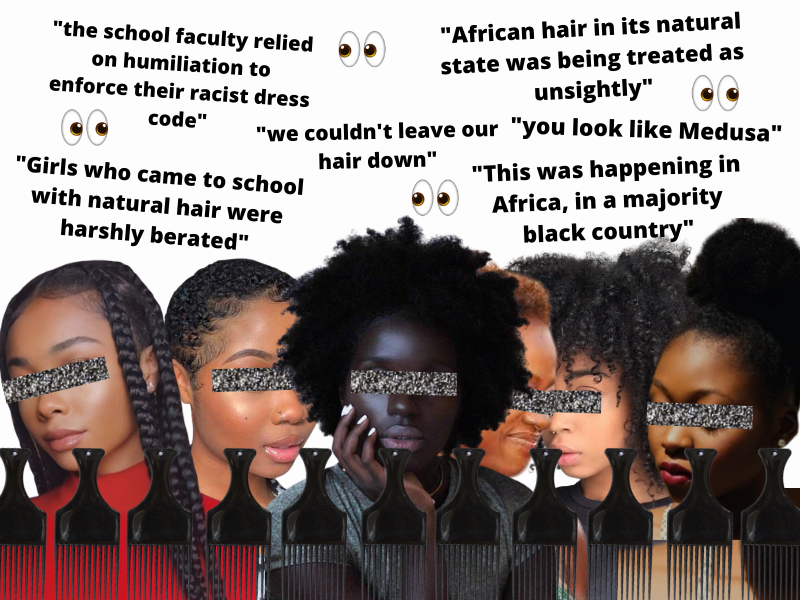

My Hair was Treated as “Unsightly”: Black Women Reveal Global Natural Hair Discrimination in 2021

My Hair was Treated as “Unsightly”: Black Women Reveal Global Natural Hair Discrimination in 2021

Funmi Ljadu IG: @artbyfunmi 23 April 21

Afro hair is often stigmatised in public spaces. Dress code policies contributes to discrimination in educational settings and places of work. The treatment of people with Afro hair in institutions within Britain and beyond, reveal a world driven by Anti-Black respectability politics. Politics that defines the acceptable way to present oneself in public. To police or punish a singular demographic, for showing up and taking space with the hair that naturally grows from their head is Anti-Black. No other race of people is subject to this kind of treatment.

Respectability politics is defined as a socio-political system under White Supremacy, which suggests that oppressed groups will be rewarded for ‘appropriate’ behaviour and presentation. The belief is, by aligning oneself with respectable aesthetics and behavioural practices, Black people can transcend their social struggles.

However, it is evident that respectability politics is a band-aid mentality, and due to the subjectivity of what it means to be ‘respectable’ and Anti-Black dehumanisation, it is clear it will never be the golden ticket out of oppression.

For instance, a Black man in America who isn’t ‘sagging’ his pants may still be stopped and harassed by police officers. But the alarming reality is that respectability politics is tied into biological features, normalising and uplifting straight textured hair, typical of white people, whilst demonising the coily texture of Afro hair.

Recently, a London-based school was embroiled in a case of Anti-Black hair discrimination. The school leadership of Pimlico Academy made plans to change their uniform policy which did not sit well with students. Specifically, they planned to ban hairstyles that could “block the view of others”, which alluded to Afro hair, and to limit the way the Hijab could be worn.

The policy was overturned, owing to the backlash and resistance shown by pupils of the school. The students staged a walkout protest which helped to make the issue public. The principal has withdrawn the proposed policies and apologised to his students.

Deanna and Mya Cook were disciplined for wearing braids at their Boston school, Mystic Valley Regional Charter. Photo credit: Vox

However, Afro hair discrimination is something that is not unique to British institutions. The international system of White Supremacy means that in Black majority nations, Afro discrimination is often commonplace. I spoke with three women who went to school in Lagos, Nigeria to explore this further.

I spoke with Adanna, whose school enforced policies of exclusion based on styles deemed inappropriate. She described her school’s regulation of Afro hair as “extremely toxic” and harmful. Adanna believed that her school faculty relied on “humiliation” to enforce their racist dress code.

She continued, “Girls who came to school with natural hair were harshly berated, often publicly and barred from events with parents, as if their hair was such an unseemly eyesore that it was detrimental to the school’s reputation.”

Adanna explained that all tradition African styles were vilified, “whether it was box braids or Afros pulled back into a bun, styles were treated with similar contempt. The situation was infused with irony on a multitude of levels, not only was Afro hair in its natural state being treated as something unnatural and unsightly, but this was also happening in Africa in a majority Black country.”

I also chatted with Kosi, who discussed her school experience of shifting hair policy that became increasingly targeted at policing natural Afro hair. She recalled these rules, saying, “My school got a new principal who became really fixated on hair. At that time my hair was texturized, almost relaxed even. So those policies didn’t really concern me, but a lot of my friends were natural at the time. I remember the principal stopped some of my friends once, and asked one of them, do you think you look good – you look like Medusa.”

Beyond name calling, the rules kept getting more intense, “She made a new rule that everyone had to have their hair tied up, we couldn’t leave our hair down anymore. The school kept changing rules on hair, at first, we were allowed to wear braids, until they restricted the length to ten inches. When I left the school and had time to think about everything that happened, I was like wow. At that time, it was just one of repressive changes the school made to police the girls. They never did anything to the boys. The principal was Black, but I think she had relaxed hair at the time.”

I also spoke to Morayo who compared hair policies in Nigeria to schools in Britain. She used to wear her hair in cornrows with a face-framing fringe. She recounted her experience, saying, “I remember a teacher literally came up to me and was like didn’t you read the school rules you can’t have your hair in your face. Then she proceeded to get me a hair clip and I had to clip my hair back.”

Interestingly, in her school in Nigeria, boys’ hair was controlled in terms of length. Morayo explained that, “boys were scolded to cut their hair when it was long with things like “are you a girl?” being said.”

She also outlined microaggressions she encountered at boarding school in the UK: “There were just a lot more comments by other girls, touching my hair and the ignorance that comes with that.”

Zulaikha Patel, 13, from South Africa has been at the forefront of the Pretoria Girls’ High protests against its racist hair policy. Photo credit: CNN

Finally, I spoke to Chidera who compared her experience of hair regulation in school in Nigeria to schools in America. She spoke on the gendered pressure on girls to conform to respectability politics: “I remember that we couldn’t have braids until year 11 and even when we did, they had to be tied up or in a bun of some sort. Schools in Nigeria seemed to be encouraging the idea that men can’t control themselves from a very young age and that somehow at the end of the day women are always to blame.”

However, she noted that natural hair was hyper visible, “in terms of natural hair, there was a lot of discrimination against people with shorter natural hair as their hair would get “rougher” quicker and the braids would get loose, so there was a lot of pressure on them to get their hair done more consistently than others because simply having it out was viewed as “unprofessional” but that wasn’t the case for people with looser curls, I think that’s another example of colourism or texturism.”

In an unexpected way, she faced less institutional pressure towards her hair in America. She told me, “In America, funnily enough, I actually felt like I could experiment with my hair more. Even though the school I went to was Catholic, they encouraged self-expression, a lot of the students dyed their hair or wore it however they liked. So unlike Nigeria, the institution wasn’t consciously trying to stop me but it’s microaggressive comments that I would get from people that weren’t exactly compliments but unnecessarily criticism, and I would only realise that later on.”

Speaking to these women about their experiences in school in Nigeria and abroad helped confirm to me the fact that Anti-Blackness is a truly global system. Despite the entrenched nature of White Supremacist respectability, there is hope yet for building a world with more tools to combat Anti-Blackness as a form of racism.

For instance, the UK-based Halo Collective are aimed at tackling Afro hair discrimination, one workplace and school at a time. By creating a ‘Halo Code’ that sets rules against discrimination, they are setting a standard around safety for Afro textured people at work. Also, the group has successfully partnered with over 60 schools and over 100 workplaces across Britain to tackle this issue.

Many more organisations have been doing fantastic work to challenge anti-black hair discrimination. In 2019, the World Afro Day report revealed that 95% of respondents wanted legal protections for Afro hair to be introduced in the UK. Also, Project Embrace has pioneered public campaigns to celebrate Afro hair on billboards.

My hope is that hair discrimination no longer has to be a common shared experience among people with Afro hair. With young people’s increased awareness of Anti-Black racism, the resistance will only grow stronger, and people will no longer have to struggle in silence.

Written By: Funmi Ljadu – a Nigerian-based collage artist and writer. In her work, she enjoys exploring her identity as well as wider socio-political issues she observes in the spaces she’s in. Visit her blog and follower her on Instagram

Header Image: @artbyfunmi